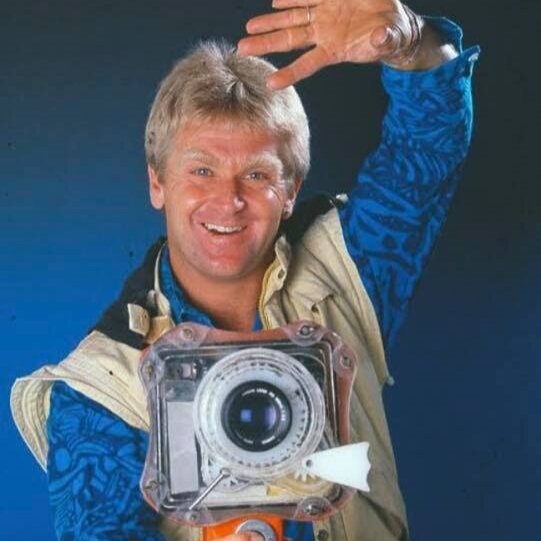

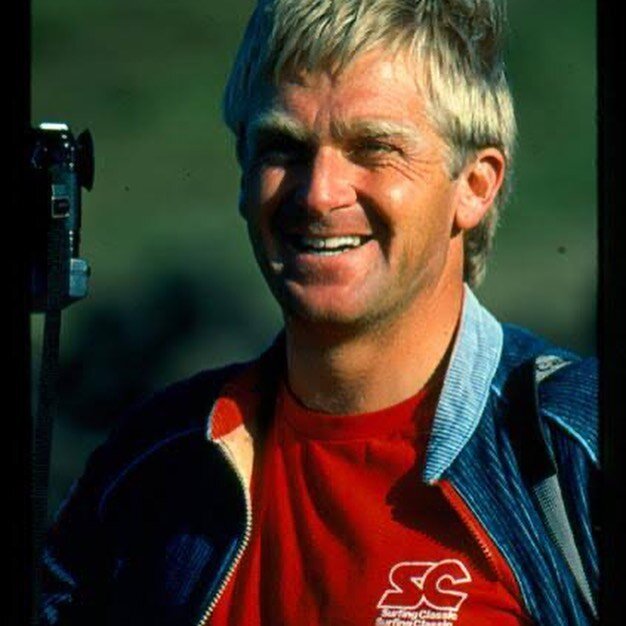

VALE MARTY TULLEMANS

Words: Tim Baker

There will never be another Marty Tullemans.

The very word unique suggests there aren’t degrees of uniqueness, that you’re either unique or you’re not, but Marty challenged that idea. He was the most unique person I ever met.

You could not be a consumer of Australian surfing magazines from the ‘70s through to the ‘90s without becoming an admirer of his work. He was photo editor of both Tracks and Surfing Life at various times. In an industry that paid a pittance, he showed a remarkable staying power and a phenomenal output, despite the meagre returns.

But it was the way he did it all that left an indelible impression on everyone he met.

Marty was tuned into a different frequency than the rest of us, heard and saw and felt and just kind of divined things that the rest of us missed, like he was a conduit to some sort of higher consciousness.

You did not simply call into Marty’s chaotic home studio looking for a shot without being prepared to spend a good part of the day helping him rifle through sheets of slides while he unpacked the mysteries of the universe for you. His rambling, running commentary on everything from the corrupt state of the surf industry to the toxicity of Australian masculinity often verged on the incomprehensible but there was always a kernel of truth at its heart. He orbited about these truths like a wayward planet that occasionally broke free of its gravitational pull and simply delved off into space.

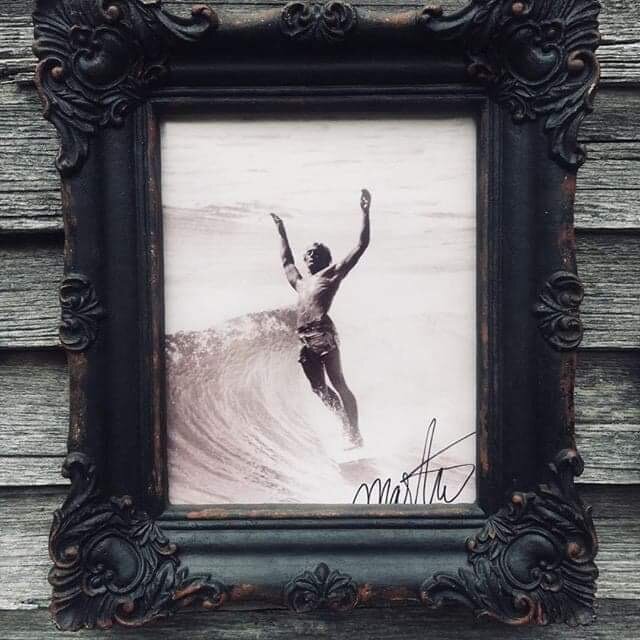

Marty Fills Us In On The Photograph Of PT's Classic Soul Arch Stance Photo (Circa 75)The Soul Arch photo is now one of the great iconic photos in surfing.

If anyone is able to assemble a truly representative exhibition of Marty’s body of work, it will blow minds. From early Michael Peterson at Kirra, Rabbit in his full world champ Muhammed Bugs posturing, through to ‘80s child stars like Jason Buttenshaw, Nick Wood or Sam Watts at the height of their extraordinary grommet powers, right through to the most arresting perspectives on the surreal perfection of Tahiti’s Teahupo’o, Marty’s output was prodigious and never mundane.

One trait I found most admirable was that Marty simply did not give a fuck what others thought. He might have been more truly himself than anyone I’ve ever met. If he felt like doing Tai Chi or waving a samurai sword in public he did, even if it meant getting arrested. When he developed a whole new surf photography rig out of an old clubbie paddle board, complete with recesses for all his various cameras and housing, he’d paddle it out in full head to toe lycra in the midst of a pro surfing contest at Snapper, mindless of whether this would be deemed appropriate conduct.

He wanted to dig deep into what was raw and real and painful and glorious and hilarious about the human condition whether his audience had the stomach for it or not. He was chess partner to Michael Peterson, for goodness sake, and what you wouldn’t give to be a fly on the wall at those little tete a tetes.

Marty travelled widely and worked with a roll call of great surfers over several generations but in MP and Kirra he had found his perfect subjects. Amongst the stacks of slide sheets and negatives and old black and white prints that stood in precarious piles in his home studio, he once showed me a rare double exposure he’d produced of MP’s head perfectly super-imposed inside a cavernous Kirra barrel. It was a piece of art that should have hung in a gallery.

Marty found the going increasingly tough as even the meagre returns from surf photography dried up as the internet took hold in the new millennia. He rented out rooms at his ramshackle Tugun home, then sold it for way below market value because of all the unapproved add-ons he’d hastily constructed over the years, and moved into an onsite van at Kirra Caravan Park, and then into an aged care facility as dementia took hold.

I visited him a couple of months back, before COVID restrictions made that impossible and it was sad and confronting to witness his decline. He had precisely zero idea who I was. Even so, he was happy enough to chat amiably for half an hour or so before he decided to lie down and take a nap. Before he closed his eyes, he leant towards me and asked in a conspiratorial whisper, “Where is this place?”

I told him he was just down the road from Kirra and that seemed to give him some kind of peace and he was soon snoring soundly.

Legendary Australia surf photographer passes away after a long battle with dementia. Heartbreaking news filtered through the surfing community this morning